Belgium is a federal state with three regions (Flanders, Wallonia and Brussels-Capital) and four language areas – the Flemish-speaking, French-speaking and German-speaking communities, as well as the bilingual Brussels-Capital area). Integrated care has been on the Belgian agenda for more than a decade. The first steps towards organising care pathways for people with chronic illness based on the “chronic care” model were taken in 2009 for patients with type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease (CKD). Contracts between patients and GPs and between patients, GPs and specialists were used to improve the interaction between these three actors. Part of the strategy was to provide financial incentives for physicians and better access to self-management materials and training for patients, as well as to support care pathways through local multidisciplinary networks. In 2012, the Belgian Health Care Knowledge Centre (KCE) presented a position paper Integrated Care, incorporating national and international research findings and the views of stakeholder groups, with more than 50 recommendations tailored to the Belgian situation.[1] After the Sixth State Reform, which came into force in 2014, the federal health minister and the federated entities agreed on a joint plan for the chronically ill “Plan conjoint en faveur des malades chroniques” based on the principles of the Triple Aim of Value Based Care (VBC). The reform envisages developing an integrated approach to medical, paramedical, psychosocial, nursing and social care, as well as a new funding model for chronic care that ensures coordinated service delivery.

The 2022 KCE study[2] on integrated care in Belgium shows a long political process with solid legal frameworks for its implementation. Critical objectives for implementation such as the WHO principles of “health in all policies”, the primacy of primary care close to home, improving continuity of care across sectors, strengthening personal responsibility and patient autonomy, better coordination of care processes, to name but a few, are firmly anchored in the policy documents. Despite the complex political structures in Belgium, the legal anchoring of the principles of integrated care is consistent across the regions. On the implementation side, however, respondents give rather poor marks. The Scirocco analysis[3] showed a mean score of 1 (0-5 for 12 dimensions) in the evaluation of the implementation of integrated care. Similar results were obtained from the patient experience survey using the PACIC instrument (patient’s assessment of chronic illness care[4] ) for the implementation of the chronic care model in Belgium. Danhieux et al. described in their study barriers and facilitators for the implementation of integrated care in Belgium amongst others the following factors on a macro level:

- Lack of common priorities among stakeholders and the absence of a clear objective at the level of the health system

- Organisational barriers such as the fee-for-service reimbursement system, fragmentation and corporatism in resource allocation, slow development of integrated e-health solutions for data exchange

- Fragmentation of responsibilities between federal and local levels complicate the implementation of a care continuum.

Within the framework of the Joint Action on Digitally Enabled Integrated Person-Centred Care (JADECARE) the Office for Self-determined Living (Dienststelle der Deutschsprachigen Gemeinschaft für selbstbestimmtes Leben, DSL) in Belgium initiated a two-pronged portfolio analysis with the aim to develop an integrated care model based on the OptiMedis original good practice (oGP):

- An analysis of routine data on hospital cases to identify variations in hospitalisation rates and to identify ambulatory care sensitive conditions (ACSC)

- A stakeholder analysis and focus group discussions to define entry points for population based integrated care.

The data supply for the secondary data analysis comprised hospital data (Agence InterMutualiste https://aim-ima.be/?lang=fr, IMA) for the years 2016 to 2019 for Belgian regions and Belgium as a whole. Hospital data for the north and south of East Belgium were available separately. Data for outpatient care were not available. The data includes information on diagnosis (ICD codes), age groups of patients, number of hospital stays and their total and mean duration, total and mean costs as well as data on ACSC cases and the possible percentage savings.

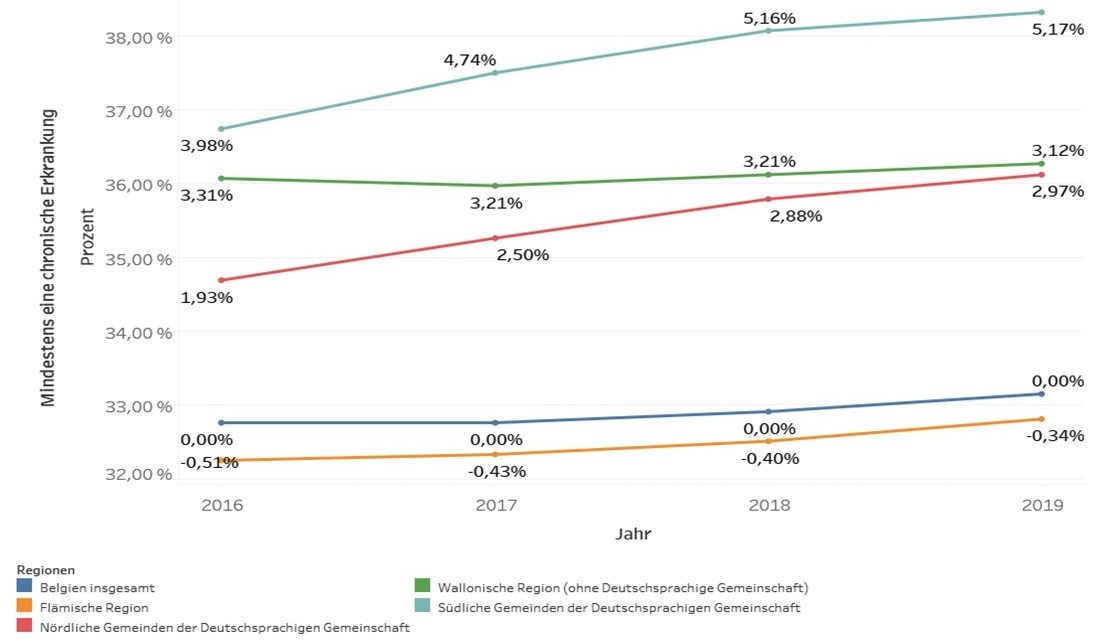

Figure 1: Evolution of chronic diseases in the Entities of Belgium 2016 – 2019 (IMA data)

The prevalence of chronic diseases has remained largely stable in Belgium over the years 2016 to 2019 (approx. 33% of the total population). The graphic above shows relative figures to the national average (the reason why the national average shows an increase of 0.0% increase although the graph shows a slight increasing over the years). This does not apply to the same extent to the different constituent entities and in particular to East Belgium. The proportion of patients with chronic diseases in East Belgium is higher than the average for Belgium as a whole. The number of patients with at least one chronic disease increased continuously since 2017. In the northern municipalities of East Belgium, the prevalence of chronic diseases is almost 2% higher in 2016 and increases to about 3% in 2019. For the southern municipalities of East Belgium, the difference is 4% (2016) to 5% (2019) for the same period (Fig 1).

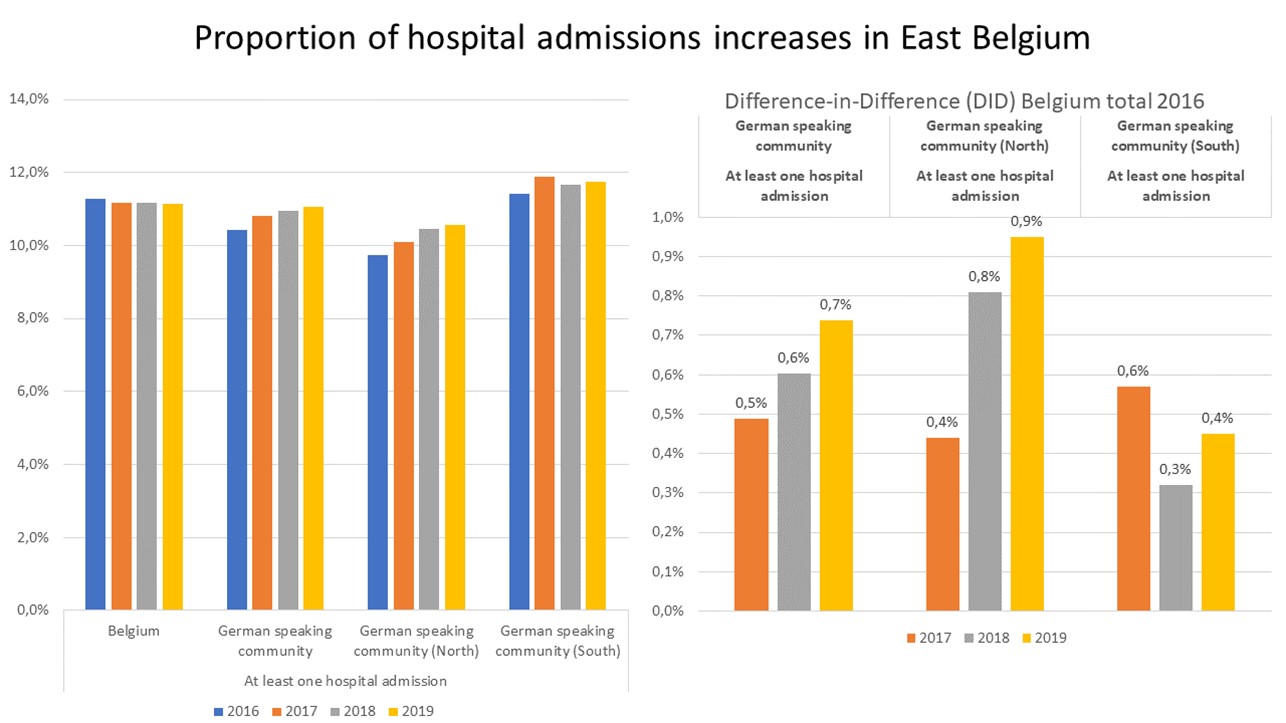

Figure 2: Proportion of hospital admissions per year and sub-state

Figure 2 shows this trend for patients with at least one admission to a hospital for the years 2017 to 2019. The Difference in Difference plot on the right side of the graphic compares hospital admissions in East Belgium to the national standard average, and separately for the north and the south of the territory. The comparison for the northern part shows a particular increase. This could indicate that at least part of the increased prevalence of chronic diseases in East Belgium is managed at the hospital level.

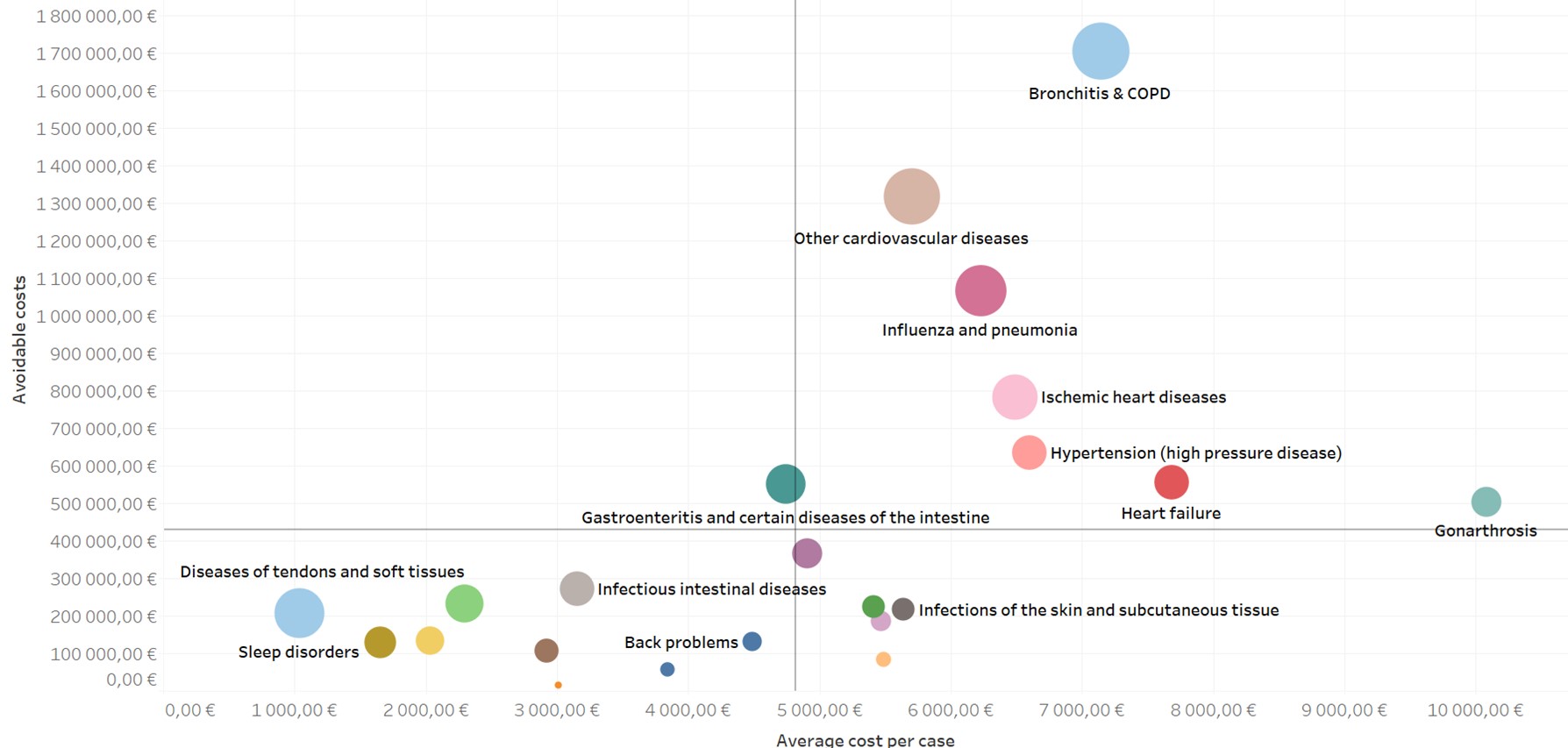

A more in-depth analyses of hospital data shows, that a considerable number of hospital admissions could alternatively be treated in ambulatory care settings or disease exacerbations requiring hospitalisation could be prevented. Figure 3 (next page) shows an analysis of ambulatory care sensitive conditions (ACSC) based on hospital data. The vertical axes shows the avoidable costs, if the disease aggravation leading to hospitalisation would be prevented or if the case would be managed in an ambulatory setting. The horizontal axes shows the average cost of hospitalisation per case. The upper right quadrant of the chart shows diseases with high savings potential (high costs and high ACSC status) with improved outpatient management. Typical diseases in this group are bronchitis and COPD, cardiovascular diseases as well as influenza and pneumonia. Cost data for treatment in psychiatric facilities were not available for analysis.

A population based integrated care health network in East Belgium would focus amongst others on the capacity for ASCS patients to be managed in ambulatory care. This includes standardised intersectoral treatment guidelines, integrated care with adapted case management, preventive measures -initially secondary and tertiary prevention to reduce the burden of disease aggravation -, patient activation measures, health programmes for patients and others. Reducing ACSC would free resources, in terms of finance and staffing, which could be invested in health programs, case management and additional preventive measures.

Figure 3: Ambulatory Care Sensitive Conditions (ACSC) East Belgium

Stakeholder consultations with a variety of actors revealed a significant interest in implementing population based integrated care in East Belgium. Interviewed stakeholders and members of the final focus group discussions suggested that:

- A much stronger link between health and social aspects is needed. Health is the prerequisite for participation in social interaction and autonomy.

- A continuous transition from inpatient and outpatient care with shortened length of stay, intermediate short-term care, linking of specialist and general practitioner follow-up care are needed. Home care models should be given preference over institutional care, also in view of the existing nursing shortage.

- Preventive care should be upgraded and firmly anchoring in patient pathways and programmes for people with chronic diseases. In addition to existing rehabilitation programmes, local associations should also be mobilised to reduce a sedentary lifestyle. A stronger linkage of primary and secondary prevention, if necessary also tertiary prevention, should be strived for. Low-threshold, non-medical care programmes for people with chronic diseases, e.g., health coaches, case and care managers.

- Prevention must be thought of from childhood, even if its successes are not immediately visible. In order to reduce cost pressure, however, a focus on secondary and tertiary prevention is necessary. Without the patient’s own responsibility and active participation, however, it is not possible. An increased commitment to patient activation and patient self-determination is needed, so that care management is more driven by patient interest.

- Integrated care cannot be sufficiently implemented in the given structure. The current service providers cannot take on any additional functions. The transformation must be coordinated and supported externally. A coordinator/integrator is needed to build and promote the health networks. Communication is seen as a central driver: the providers must be able to continuously learn from each other, which requires a regular exchange of experience.

- For chronic patients in particular, there is a need for a motivator and companion, a health contact point, educators and practitioners, case and care management. One solution could be low threshold contact points close to home, e.g. health kiosks.

- Digitalisation must continue to advance with good basic conditions and involve the patient. Stronger implementation of the e-health strategy and networking along patient pathways also beyond medical actors is needed for a solid and detailed evaluable database for control, stronger outcome orientation in care and definition of relevant indicators.

The OptiMedis original good practice (oGP) suggests incentives to be changed to focus on keeping people healthy. Prevention and health promotion, activation of patients are essential factors. Targeted care management, especially of the chronically ill, reduces the exacerbation of illness and the need for hospital admissions. The incentive systems include the treating physicians (more time for detailed patient counselling with regard to their health goals), hospitals (support in the reorganisation of smaller hospitals), patients (free access to health programmes) and communities (local health teams support in keeping the inhabitants healthy).

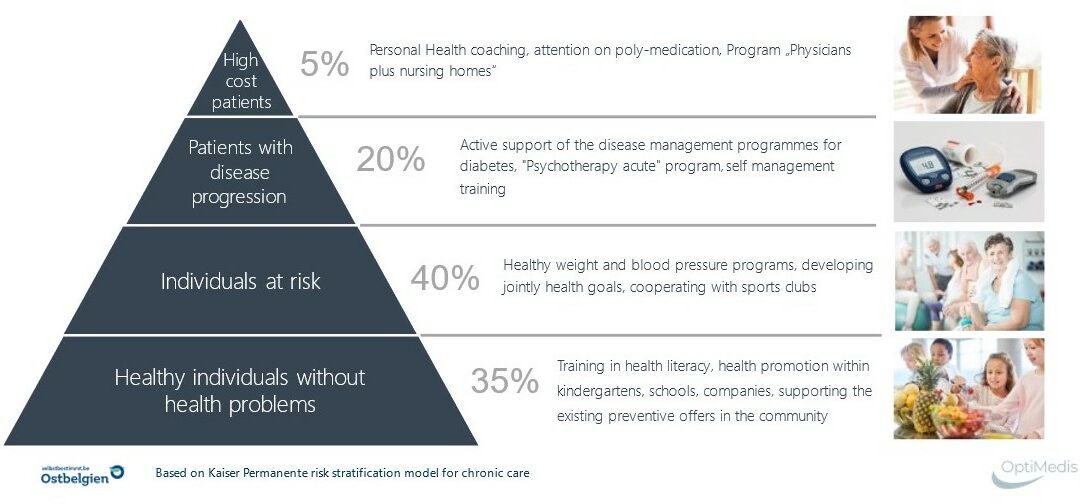

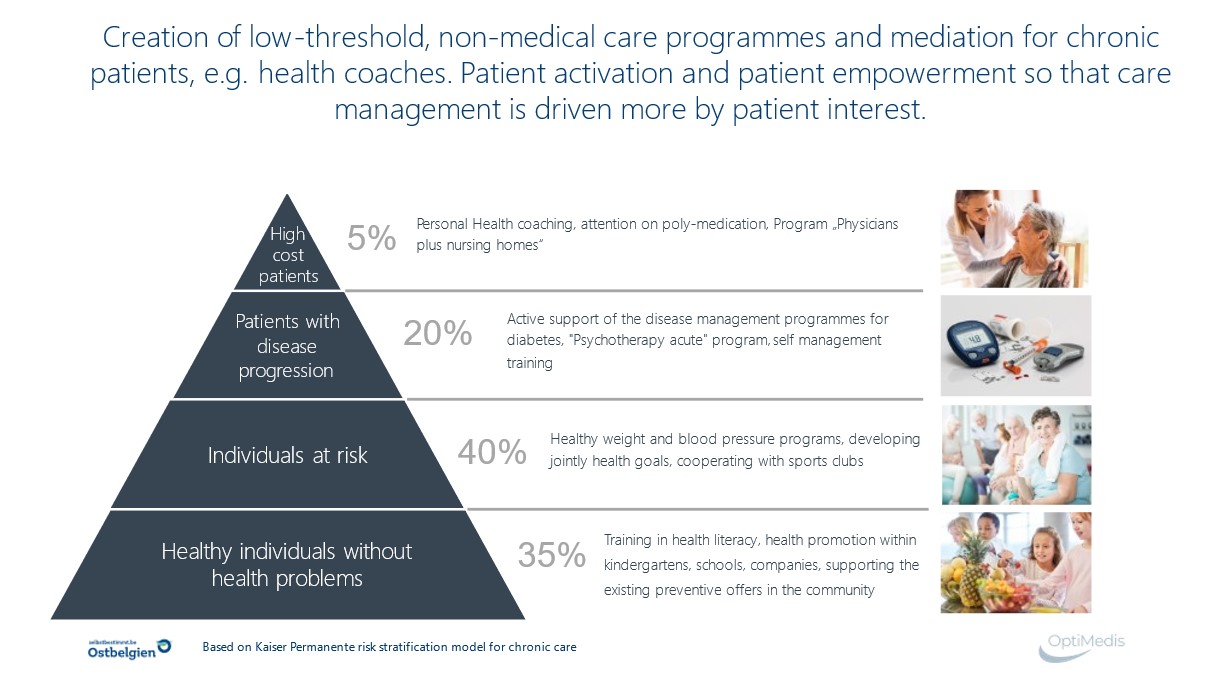

Appropriate interventions require rather homogenous population groups to better target interventions. The Kaiser Permanente risk stratification model shows different risk strata, which each require a specific set of interventions. Low threshold, non-medical health programs need to be developed to empower and mobilise patients to engage in their proper health. The below graphic (figure 4 is adapted for diabetes type 2 patients).

Figure 4: Adapted Kaiser Permanente patient segmentation pyramide

The typical set of interventions for healthy individuals with a disease disposition is geared towards increasing health literacy, primary prevention at community levels and health promotion at community, school or occupational levels. For individuals a risk or early stage of disease, interventions require appropriate medical care and specific health programs, controlling weight or high blood pressure, increasing physical activity, reducing health risks (smoking reduction, etc). Patients at risk of disease progression require concrete medical interventions, support programs for self-management, psychosocial support, and others. The smallest group are the high-cost patients with little possibility for preventive interventions and a strong focus on appropriate poly-medication.

The typical segments for integrated care are the middle segments with their ability to reduce disease aggravation and improve quality of life and well-being. These segments can produce the efficiency gains anticipated by integrated people centred care programs. Savings can be generated with this type of patients, which may finance preventive activities. Primary prevention and health promotion are typical interventions for the lowest strata in this pyramid. Although worthwhile interventions, efficiency gains materialise only in the longer run.

The assessment suggests a reorientation of care towards a Population Health Management (PHM) approach with a stronger focus on outpatient care for chronically ill and multimorbid patients, intensification of prevention with care programmes aimed at avoiding disease exacerbation and hospital admissions. The value-based care (VBC) system with its quadruple or quintuple aim can serve as indicator framework to measure value added. In the sense of the chronic care model, this includes informed patients who have all the important resources to better self-manage their illness and play an active role in the treatment process. For the development of a future health territory of East Belgium, there are still further questions to be answered regarding the legal framework and the access to appropriate data within the current reform agenda and the available resources:

The JADECARE project activities prepared the ground for a policy dialogue process, with the aim to design and implement a population based integrated care model based on the OptiMedis oGP. The plan is anchored in the health strategy of the Ministry of the German speaking Community and concrete consultations with the Belgium Ministry of Health or ongoing.

[1] Paulus Dominique, Van den Heede Koen, Mertens Raf. Position paper : organisation of care for chronic patients in Belgium. Health Services Research (HSR). Brussels. Belgian Health Care Knowledge Centre (KCE). 2012. KCE Reports 190C. KCE_190C_organisation_care_chronic_patients_Position Paper_0.pdf

[2] Lambert A-S, Op de Beeck S, Herbaux D, Macq J, Rappe P, Schmitz O, Schoonvaere Q, Van Innis A.L, Vandenbroeck P, De Groote J, Schoonaert L, Vercruysse H, Vlaemynck M, Bourgeois J, Lefèvre M, Van den Heede K, Benahmed N. Towards integrated care in Belgium: stakeholders’ view on maturity and avenues for further development. Health Services Research (HSR) Brussels: Belgian Health Care Knowledge Centre (KCE). KCE Reports 359, D/2022/10.273/xx. ß

[3] https://www.sciroccoexchange.com/uploads/SCIROCCO-Exchange-Translated-Maturity-Model-German-v0.3.pdf